Pope Francis’ reign deeply shook the Catholic Church. For over a decade, his emphasis on standing by the poor marked a new path for the Church. He urged the Church to step out of its comfort zone and “pitch tents among the marginalized.” Pope Francis initiated discussions on topics previously considered taboo in the Catholic Church, such as open debates on women’s roles.

He recognized LGBTQ Catholics as “children of God,” allowed divorced and remarried individuals to rejoin religious practices, strongly criticized economic inequality, and highlighted environmental protection.

However, throughout his papacy, he faced fierce opposition. Some conservative Catholic groups staunchly opposed him, while many high-ranking bishops were either indifferent to his reforms or silently resisted them.

Now, as the 133 voting members of the College of Cardinals prepare to elect a new pope in a secret conclave, they face a crucial decision: either advance Pope Francis’ reforms and vision or slow down and revert to the old ways.

To understand the dynamics of the papal election, CNN spoke with several cardinals and key Church figures. Many want a candidate who prioritizes unity. However, a close associate of Pope Francis warned that electing a “safe” candidate would be a “kiss of death” for the Church.

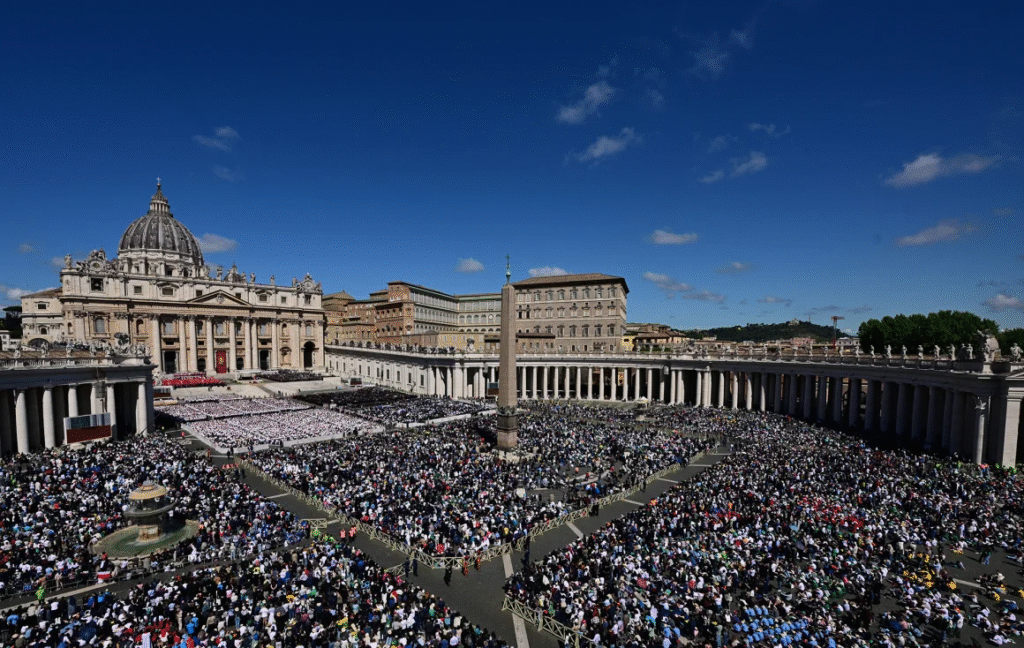

Those participating in the conclave at the Sistine Chapel on Wednesday have undoubtedly witnessed the outpouring of public love following Pope Francis’ death.

When Cardinal Giovanni Battista Re, dean of the College of Cardinals, spoke about Pope Francis’ philosophy during his funeral, the crowd in St. Peter’s Square repeatedly applauded in support. In East Timor, where Francis visited in 2024, nearly 300,000 people gathered in prayer on the day of his death. A retired cardinal later urged others to heed these messages.

Cardinal Walter Kasper, once Pope Francis’ theological advisor, told Italy’s La Repubblica: “God’s people have already voted at Francis’ funeral. They want his path to continue.” In other words, the Church must read the signs of the times.

Supporters of Pope Francis believe only someone willing to advance his work should become pope.

However, papal election politics are subtle. Open campaigning disqualifies a candidate. Cardinals must discern God’s will before voting—though this doesn’t mean they’ll vote after mere prayer.

During pre-conclave meetings, cardinals gather every morning at the Paul VI Hall for “general congregations,” then spend evenings discussing pasta and wine. Many dine at Borgo Pio, a small village-like area near the Vatican.

Divisions are already emerging. Some cardinals want the next pope to follow Francis’ path, emphasizing the Church’s global diversity, as its center is no longer Europe or the West. Others call for “unity”—a coded plea for predictability and stability.

Vatican biographer Austen Ivereigh explains these two positions:

“The first group, the ‘diversifiers,’ see Francis as the first pope of a new era, showing how to evangelize today while embracing differences. The second, the ‘uniters,’ see his papacy as an aberration and want to return to a unified path.”

Among the “uniters” is Cardinal Gerhard Müller, a fierce critic of Francis and former head of the Vatican’s doctrinal office, whom Francis removed in 2017. Müller recently told *The New York Times*: “All dictators divide society,” indirectly criticizing Francis’ papacy.

Most cardinals disagree with Müller, praising Francis’ empathy for the marginalized and his ability to connect with ordinary people. Yet many now rally behind “unity,” criticizing Francis for reforms like the Synod, which questioned women’s roles and Church power structures.

Some cardinals were also frustrated by Francis’ critiques of clergy obsessed with lavish attire or his call to bless same-sex couples—a move rejected by African bishops.

This “unity” camp includes retired cardinals who hope the next pope will be less disruptive and more stable.

Cardinal Vincent Nichols of Westminster told CNN: “A pope’s first duty is to protect and deepen Church unity.” While praising Francis’ people-centric approach, he added, “Now, some balance may be needed—not in doctrine, but in governance.”

The “unity” faction’s leading candidate is Cardinal Pietro Parolin, the Vatican’s secretary of state. He doesn’t oppose Francis’ work but has a different leadership style—a calm, thoughtful Italian diplomat who negotiated the Vatican’s provisional deal with China on bishop appointments.

Critics, however, say Parolin lacks grassroots experience. His speech at a youth prayer vigil after Francis’ death—read from notes—felt disconnected compared to Francis’ spontaneous, lively engagements.

Yet Parolin has strong backing in Vatican diplomatic circles. Retired Italian Cardinal Beniamino Stella, once close to Francis, shocked cardinals on April 30 by criticizing Francis for involving lay people in Church governance, arguing that ordination and governance shouldn’t be separated.

Some argue “unity” sounds good but is misguided. Cardinal Michael Czerny, a close Francis ally, warns: “The worst danger is making unity an absolute goal, leading to uniformity—the very thing we’ve spent decades trying to move beyond.”

He adds, “Unity and uniformity may sound similar, but the difference is vast. One is a kiss of death; the other is life—vibrant life.”

The People’s Will

During the nine days of mourning, cardinals led nightly prayer services reflecting on Francis’ legacy. Criticizing him openly became difficult as many asked: How do we continue his work?

At one service, Cardinal Baldassare Reina of Rome said: “Francis’ reforms went beyond religious identity. People saw him as a universal pastor. Now, they wonder: What will happen to these reforms?”

This need for continuity favors reformist candidates like Cardinal Mario Grech (head of the Synod office) or German Cardinal Reinhard Marx. Luxembourg’s Cardinal Jean-Claude Hollerich, a key Synod figure, also supports a Francis-style pope.

A “diversifier” candidate could come from Asia or frontline Church work, such as Philippines’ Cardinal Luis Antonio Tagle—though he’s not the only possibility.

Predicting the Outcome Is Hard

The voting cardinals are a diverse group from around the world. Francis appointed cardinals from previously unrepresented countries, creating a new dynamic.

But this diversity means many don’t know each other well. Name badges are used during discussions, and the intense media scrutiny has unsettled some.

Predicting such a diverse group’s vote is tough. However, many non-European cardinals align with Francis’ vision, particularly on global crises.

Myanmar’s first cardinal, Charles Bo, appointed by Francis in 2015, hopes the next pope will “walk steadfastly on the path of peace” and become a moral voice to “pull humanity back from the brink.”

He adds: “Religions must work together to save humanity. The world needs a new breath of hope—a synodal journey choosing life over death, hope over despair. The next pope must be that breath of hope!”

In the coming week, those entering the Sistine Chapel won’t just vote for a new pope—they’ll make a decision that will shape the Catholic Church for decades.

Read More : What strategy did Zelensky use to lure Trump?